Why does Colombia have so many street-children?

The background to the Colombian street-children is a complicated one, and it affects children of all ages. Whenever a child leaves his or her home, there is aways a specific, individual cause, but there are also some ‘general’ causes, which reoccur again and again and it is worth looking at these.

How we used to find many children in the city’s streets.

First, however, it is necessary to dispose of the myth that the problem of street-children in Colombia is the result of an exploding birth-rate in a mainly Roman Catholic country. According to the Total Fertility Rate figures supplied by the United Nations, in the period from 2005 to 2010 Colombia was ranked 109th out of 195 countries, with an average of 2.22 children per woman of child-bearing years. In comparison, women in the three countries at the top of the list had an average of more than 7 children each. The United States was ranked 126th, with an average of 2.05 children per woman; and the United Kingdom was ranked 148th, with an average of 1.82 children per woman.

Although the surface area of Colombia is about 4.6 times that of the United Kingdom, it has a population of only about 45,000,000,whereas that of the United Kingdom is about 61,000,000. Colombia is certainly not over-populated, and the rapid, well-established and continuing decline in the birth-rate there is an alarming trend which may well result in a future “demographic winter”, with more and more elderly people being supported by fewer and fewer young ones. So, it would be a great mistake to imagine that the problem of street-children in Colombia has been caused by its citizens having had too many children.

So, what are the pressures that force children onto the streets?

1. Violence

In 1948 a period of virtual civil war known as La Violencia (The Violence) started in Bogotá and quickly spread to the countryside. Various groups of guerrillas were formed and more than 300,000 people were killed. Although La Violencia officially ended in 1953, it started a movement of thousands of peasants from their lands into the cities, and this migration has never stopped. In the 1970s various paramilitary groups were formed and fighting between them and the guerrillas often took place in the country areas, with the peasants being caught inbetween. In the 1980s and 1990s there were many massacres, forcing even more peasants to flee to the cities. Other families found themselves threatened by groups of guerrillas or paramilitarias and forced, often at the end of a gun, to leave their homes. Many experienced the loss of their children, particularly girls, as they were taken for forced military service by guerrilla or paramilitary groups. Many were injured or killed by the mines laid to protect the drug crops and destroy the army. This, plus the continuing war against drugs, has forced many thousands of refugees to flee from the countryside into the cities.

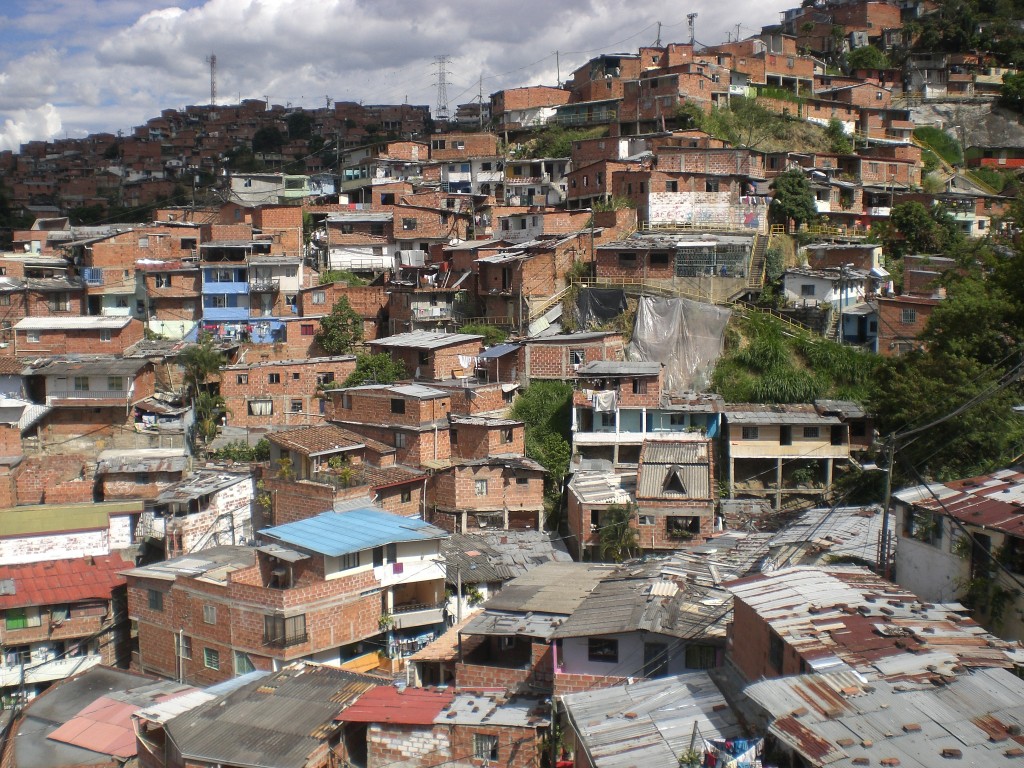

Shanty-town in Medellín—-home to some of those displaced by the violence.

Shanty-town in Medellín—-home to some of those displaced by the violence.

2. Poverty

When the peasants arrive in the cities they have nowhere to live so they build shacks for themselves in the shanty-towns. Here, the very violence from which they have fled has broken out and is beyond control. Most of this violence is related to drugs and the fight for control of the drugs trade. Many young people join the bandas ( street gangs) and there is a constant threat of battles between them, as they fight for supremacy. Add to this the many criminal gangs that abound in the city and the result is a level of violence that is incredibly high. Life is cheap; of no value whatsoever.

In this setting live the thousands of people who have fled the violence of the countryside, and the ultimate victims of this situation are the children. Their lives are uprooted when they have to escape the violence of the countryside often having to leave all their possessions behind. Sometimes their families break up, as when one or both parents are killed or are forced to run away. Children orphaned in this way usually end up living in the streets.Not only does this mean that children are deprived of their education, there is also the problem of what they do in the daytime. If their parents have work the children who don’t go to school are either locked in the house eland ay or sent out into the street.

In this setting live the thousands of people who have fled the violence of the countryside, and the ultimate victims of this situation are the children. Their lives are uprooted when they have to escape the violence of the countryside often having to leave all their possessions behind. Sometimes their families break up, as when one or both parents are killed or are forced to run away. Children orphaned in this way usually end up living in the streets.Not only does this mean that children are deprived of their education, there is also the problem of what they do in the daytime. If their parents have work the children who don’t go to school are either locked in the house eland ay or sent out into the street.

In many ways street-life can appeal to a child’s sense of freedom and adventure, and so it is not surprising that it is often more attractive to them than life at home in the shanty-towns. Once in the street they are prey to all its dangers: violence, crime, drugs……..and once captured by one or more of these they are unlikely to go back home.

The violence affects the lives of children in other ways too. The flight of peasants from the coutryside to the cities has increased the population of the cities enormously. Not only are there no houses or jobs for the refugees, there are not enough schools either. In Colombia the schools have 3 sessions a day: morning, afternoon and evening, but there are still nowhere near enough school places for all the children.

Violence in the home:

Child labour is illegal in Colombia, but if a family is very poor the children often have to start working in the street in order for them and their family to survive. Most Colombians are generous and so the most common activity is begging, but the children also sell things, wash car windscreens, juggle and generally use whatever skills they have. At first they normally go home at night but working on the street leads them to make friends with other

children and adults who are living there. If they go home they have to hand over any money they have earned to their parents. If they have not earned enough they may be beaten so it isn’t surprising that some of them decide to stay in the street with their new friends and keep the money themselves. They then risk being drawn into real street-life with all its dangers. Working in the street is the most common route to living in the street full-time.

children and adults who are living there. If they go home they have to hand over any money they have earned to their parents. If they have not earned enough they may be beaten so it isn’t surprising that some of them decide to stay in the street with their new friends and keep the money themselves. They then risk being drawn into real street-life with all its dangers. Working in the street is the most common route to living in the street full-time.

Although most Colombian parents are loving and reponsible, sometimes children runaway from home because of the mental, physical or sexual abuse that they have had to endure there. In many cases this is due to the breakdown of the family unit, for about one third of Colombian children do not live in a secure family. If parents split up, or if one dies, a step-father often comes onto the scene. He may well refuse to accept someone else’s children or he may abuse them. He may even force the mother to abandon them and leave them on the streets. In other cases women who have been treated badly may become abusers and mistreat their children. Some children are abused because their parents have turned to drink or drugs in order to blot out the poverty and misery of their lives. A Government report said that 70% of street-children had been beaten when they were at home.